Buying a 57-year-old typewriter

Yes, I’m completing my transformation into That Guy CLUNK CLUNK DING

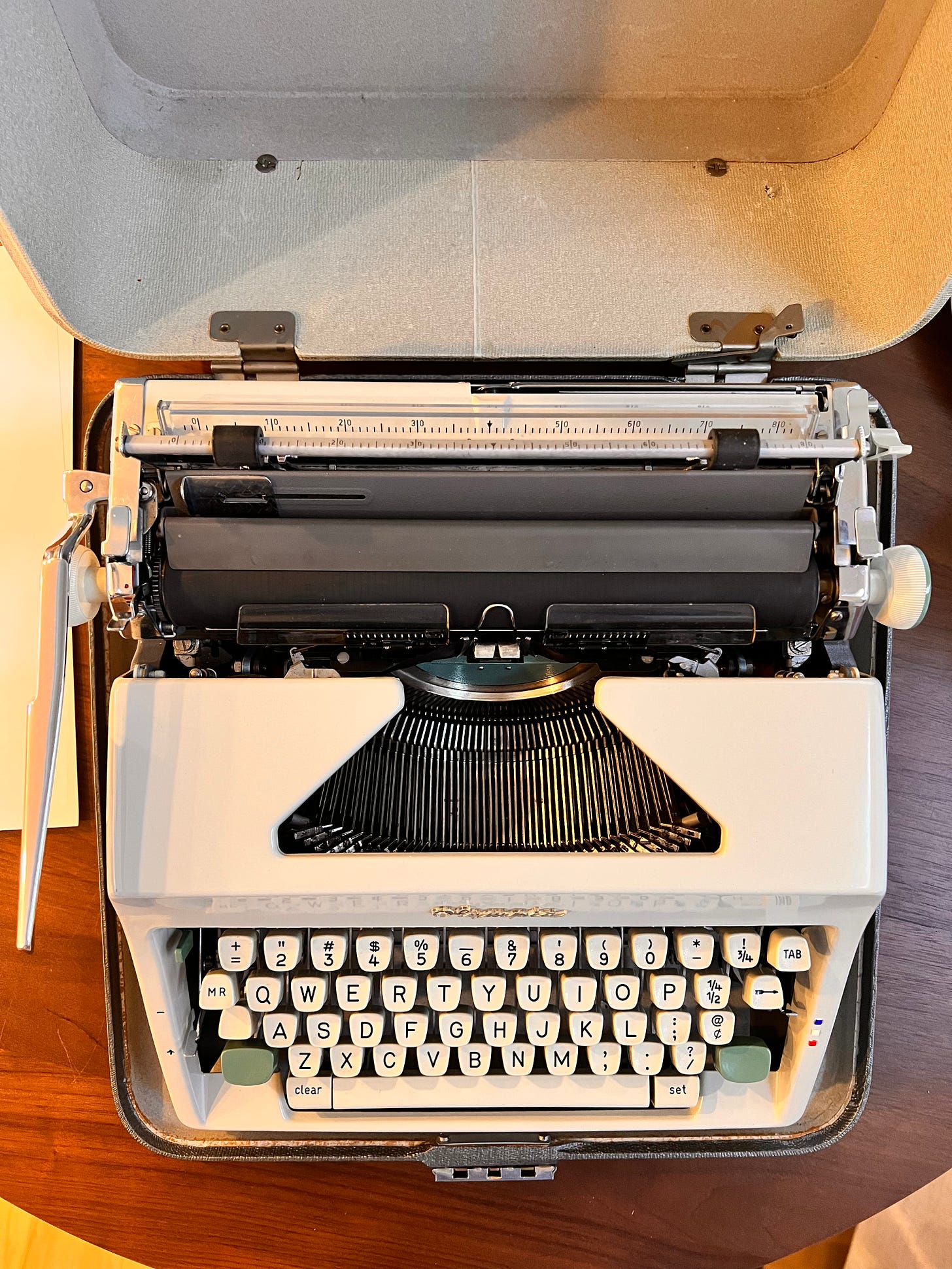

Pictured above is a 1965* Olympia SM9 portable mechanical typewriter. This is also my 1965 Olympia SM9 portable mechnical typewriter, as I just bought it. And no, I did not transcribe this email from the typewriter, as I am not completely insufferable (yet).

*1965-ish. +/- a couple years — I need to look up the serial number

Remember the first time you drove a car with a manual transmission? How unforgiving the clutch felt as it bucked you forward and all your pride right up from your stomach with it (ok, maybe just me)? But then, when you finally started from a stop successfully: “Slowwwwwly release the clutch, feel the bite point, the car moves! We’re doing it! Clutch innnnn, grab the shifter, pull down to second and feel the lever ~notch notch notch~ into gear, and let the clutch outttttt — buh-bump — a little rough, but in concept we’ve got this! Forward momentum is achieved!”

If you’ve never used a mechanical typewriter, I would very much liken the experience to having driven an automatic transmission your entire adult life — as skillfully and well-practiced as you can — and then being tossed into a little old British sports car with a 4-speed that doesn’t even have synchromesh.*

*Modern manual transmissions allow you to shift from any gear to any other gear using a technology called gear mesh synchronization [synchromesh]. Before synchromesh, you had to shift sequentially (1-2-3-4-5, which is as you’d do today, but also 5-4-3-2-1 to a stop — clutching in and out on every. single. downshift. Every time. Having driven both types: Unsynchronized gearboxes suck! They’ll also wreck your left thigh.)

Weighty words

If anyone had any illusions (I might have, I’m not terribly sure): Typing on a mechanical typewriter is absolutely nothing like typing on a mechanical keyboard. Truly, the two experiences could not be more different (and if they were, I would probably give up).

I am sorry to break this to anyone with romantic notions about their clicky-clackies — and I say this with love, I adore my mechanical keyboards! — but your digitally tracked keystrokes would rightfully elicit a “oh sweet summer child” the moment you’d compare the two. It’s not even worth trying!

So, what’s it like? First, think back: Did you ever play with a mechanical cash register as a kid? We had an antique one in the house (don’t ask why, I don’t even know), and I remember that even that old, broken thing had a few keys that still gave good thunk. You could feel the weight of the spring resisting you, the metal bar swinging the hammer to the strike plate — but it was vague and heavy and empty, like shifting a car with the engine off. It gives you a sense in principle, but it’s nothing like driving.

The next-closest to typing on a typewriter is playing an upright piano. I am deadly serious. The first commercially-sold typewriter* anyone would successfully identify as a typewriter was prototyped using piano and telegraph parts, including piano hammers and keys. While this invention in 1867 has seemingly little bearing on what a typewriter would be and feel like 100 years later, the truth is that a mechanical typewriter is more musical instrument than neutered electronic gizmo. Of course, electric typewriters changed all that, and they’re their own world of fascinating history and development. The IBM Selectric to me remains so cool! The golf ball!

*The Sholes and Glidden typewriter is, for all intents and purposes, the first typewriter in the way the Apple II was the first personal computer. It was the first one that “normal” people would meaningfully buy. And importantly, it set the basic design principles for typewriters for many years to come. It wasn’t the “first” in as many technical senses, but it was the first machine of its kind that worked well enough for “normal” people to pay attention. Much like the Apple II! I also find it very cool that the typewriter is a decidedly American-led innovation, even if its foundations and principles are rooted in ideas and inventions from around the world (again, much like the personal computer!).

Typing time

But back to the Olympia SM9. Typing on a mechanical typewriter requires a very different posture and thought process than using a keyboard, for one. Your fingers cannot afford to more than brush another key as you type, because it’s incredibly easy to fat-finger and get the key hammers stuck on each other (which frequently results in neither key striking). You must then “unstick” the hammers, hit backspace, and continue mid-word. Is the clutch and shifter analogy starting to click (or clunk)? I hope so!

The keys themselves are stepped in a manner that I’d liken to walking in Lisbon: Very vertical. Your fingers truly must leap from key to key, and hover above the rows to ensure your accuracy isn’t compromised by an incorrect approach angle (i.e., striking another key because your finger isn’t “vertical” enough, causing you to bump up against or press down on a second key). It feels as though you should have little strings hooked into your hands from the ceiling, to keep your wrists up and fingers pointed down. Again: Like playing a piano.

This was a light bulb moment: It explaned a lot to me about the very odd way old people type. The hunt and peck — it’s quite understandable if you’ve only ever used a typewriter and then suddenly decided to learn how to computer.

On a typewriter, your mistakes are truly, visibly on the page unless you have a correction ribbon (a feature exclusive to electric typewriters). Otherwise, you have to use white out (messy!) or correction tabs — a small paper card insert covered in a white chalky substance that the key hammer strikes over the black ink on the page. If you’re thinking “that doesn’t sound very efficient or easy or even good?” — you are correct! It’s positively primitive. I can imagine my typewriter saying, stodgily: “It’s also what you get, you ungrateful heathen! Could be worse, you could be scrawling all your thoughts in pencil!”

This means your keystrokes must be intentional, distinctly sequential, and that spelling must proceed with absolute confidence in your personal dictionary. Otherwise, you might want to keep your phone handy or ask Google how to spell “bureaucratic” because I know I’m going to mess it up every damn time. I think we’ve all got those words, and a mechanical typewriter will make you acutely aware of which ones they are!

Clunk clunk DING

The feel, the sound, the ever-so-slight orchestrated mechanical violence of the key hammer striking the page? It’s like nothing else. My mind goes to a very different place in front of the typewriter: Immense, almost intimidating focus. There is no browser tab, there is no “quick Google,” there is no “check on that for a second.” It’s you and the keys and the page, and that canvas offers no distraction. If anything, a typewriter asks something of you: “If you are not here to put word to page, then why are you here?” There are no compelling alternatives.